"Sunday Morning" opens the album with the deceptive surface calm of a tingling celeste played by Cale (the instrument was just lying around the studio) and the limpid hum of his overdubbed viola. In fact, it's a paranoiac morning-after blues, "a song about how you feel when you've been up all Saturday night," according to Morrison, "and you're crawling home while people are going to church. The sun is up and you're like Dracula, hiding your eyes."..."It's pretty paranoid," Reed admits. "My friend Delmore [Schwartz] once said, 'Even paranoids have enemies.' The song is kind of about that: 'Watch out, the world's behind you.' Possibly for real."

I usually felt more pleased than paranoid when going home after a long night out in NYC--but being a small Caucasian female, and most often a dateless one at that, I was constantly aware of the need to watch my back. The song eloquently encapsulates this nightlife's/morning after-life's blend of euphoria and foreboding. As such, now we'll discuss a nightspot that the VU made their own, only to have it snatched out from under(ground) them.

THE DOM/STANLEY'S/BALLOON FARM/ELECTRIC CIRCUS--23 St. Marks Place b/w 2nd and 3rd Avenues. Although the official address for these clubs is usually given as 23 St. Marks, they were housed in a row of affiliated buildings at 19-25 St. Marks--and the row had a long, convoluted history well before it was a gleam in Andy Warhol's eye. Here's an excerpt from a November 6, 1998 New York Times "Streetscapes" column by Christopher Gray entitled "19-25 St. Marks Place: The Eclectic Life of a Row of East Village Houses":

In 1833 the developer Thomas E. Davis built three neo-Federal houses at 19, 21 and 23 St. Marks Place...[I]n 1870 the Arion Society, a German singing and musical club, bought 19 and 21 St. Marks Place, and their architects, Schulze and Schoen, added a mansard roof and additional door trim. In 1874, The New York Times reported that at the society's annual carnival, which included a musical skit lampooning William Marcy (Boss) Tweed, members were required to wear hats in the shape of dolphins. By the 1880 census the house next door, 23 St. Marks Place, had been turned into a multiple dwelling...In 1887 the Arion Society moved up to a new clubhouse at 59th Street and Park Avenue and George Ehret, a brewer and real estate investor, bought 19 and 21 and, next year, 23 St. Marks Place. He joined the buildings and leased them out as a ballroom and community hall, which became known as Arlington Hall.

Gray neglects to mention Arlington Hall's most notorious incident, which happened on January 9, 1914--a territorial shootout between rival Jewish and Italian gangs, led by "Dopey" Benny Fein and Jack Sirocco, respectively. Details of the occurrence can be read here, but for our purposes let's return to Gray:

In the 1920s the Polish National Home bought 19, 21, 23 and 25 St. Marks Place, combining the four buildings to house Polish organizations and a Polish restaurant open to the public. By the 1950s this section of Greenwich Village was attracting the Beat Generation. Stanley Tolkin, a bar owner, took over part of the complex--apparently the basement area of 19 and 21 St. Marks Place--as a performance space. The Fugs, famous for songs like "Group Grope" and "Slum Goddess of the Lower East Side," often performed there.

Tolkin was the proprietor of another bastion of Bohemia, Stanley's Bar at 13th and Avenue B. John Gruen's The New Bohemia (New York: A Cappella, 1966) offers this characterization of him:

Describing himself as an East Villager "since the year one," Stanley (as everyone calls him) is a congenial old-timer given to talking out of the side of his mouth. A friend of the artists, a shrewd businessman, and a father-confessor to the troubled of New Bohemia, Stanley has watched the growth of the area with as much amazement as other local residents. That he has so wisely responded to the impulses of the Combine Generation must be attributed to his acumen for very early noting the shifts in the area's social and artistic climate.

From what I gather, there were two different (yet related) mid-'60s bars in the same 19-25 complex. Stanley's was smaller, and since it's usually described as being "downstairs" I'm guessing it was situated in the basement. I'm not quite sure which floor the Dom was on--photos from the era show the Dom's entrances at the ground level, but it's often described as being on the second floor. It took its name from the Polski Dom Narodowy, and presumably occupied what had been the Polish Home's (and Arlington Hall's) ballroom space. Those same photos show "Polski..." signs on the first above-ground floor (with separate doorways accessible from stoops), so I assume the Polish National Home maintained some facilities at 19-25 while the Dom was in action. Here's an account from Lorenzo Thomas in Ronald Sukenick's Down and In: Life in the Underground (New York: Collier, 1987):

There was a big upstairs dance hall, and there was...the downstairs section where the food and stuff was prepared for the dances held up in the dance hall...Stanley made a bar out of it...Now it already had a long bar in there, and there was a huge room next to it. He installed all these tables in there, and for the first night of the opening he leafletted Stanley's [the original at 13th and B] announcing this affair, and of course the word was all over the street, and the opening night he served draft beers for a nickel. So you can tell what the result was. The entire Lower East Side, all the painters, all the poets, everybody in the world showed up...The place must have had five hundred people in it...Everybody was there, every different magazine grouping or workshop grouping, all of the various painters, musicians, in other words it was like the entire East Side simply turned out in one place at one time for the opening of this new joint...There was no entertainment...After that they began to do things like live music. They had jazz, they had bands that played back in the larger room for dancing...[Then it] became a jukebox disco place, and the population changed from the East Village people to mainly Black kids and the box was mainly soul music.

And here's a description from The New Bohemia:

The most dynamic of the New Bohemia bars has been the Dom...[which] opened a little over a year ago and immediately became the central meeting ground of the New Bohemia. On any night the large, dark dance floor is an impenetrable forest of couples jumping, twisting, gyrating to the music of a perpetually fed jukebox. Young Negroes ask white girls to dance, and are never turned down. The music heightens everyone's need for action, motion, and release. The Dom's long and roomy bar is lined with young people whose faces reflect the excitement of the place. The talk is animated, and the sense of exhilaration that pervades the place makes of everyone a potential friend and lover.

Steven Watson's Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties (New York: Pantheon, 2003), is rather less effusive:

The Polsky Dom Narodny [sic] was an East Village Polish wedding and social hall (Dom is Polish for "home") with a high stage on the second floor, a bar, and even a balcony. But the charmless space had no lighting system and smelled of cat urine. In 1966 St. Marks Place was just evolving into the edgy East Village, and the only vaguely hip establishments on the block were a soda fountain called the Gem Spa and Khadejha, a shop for African-style dresses.

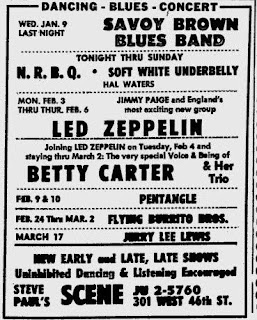

These conditions didn't deter Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey. They were looking for a space to put on a series of multimedia happenings, replete with films, light shows, dancers, and their new "house band," the Velvet Underground. There had been tentative plans to associate with a new discotheque built inside an old airplane hangar-turned-film studio on Long Island, to be called Andy Warhol's Up. But the disco's owner, Broadway producer Michael Mayerberg, apparently balked at the dark glamour of the Factory crowd and the scary sounds of the Velvets; he opted to call his place Murray the K's World and open with the established Rascals instead. [As quoted from Popism: The Warhol '60s in the previous post, Warhol actually attributes the "Up" scenario to an aborted affiliation with the Cheetah. Elsewhere in Popism he states that the proposed association with this Long Island disco would have led to it being named Andy Warhol's World--and supposedly the airplane hangar in which the disco was situated had once housed Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis.] On a suggestion from artists Jackie Cassen and Rudi Stern (who had leased the Dom for their Theater of Light events), Warhol and Morrissey scoped out the Dom, liked what they saw, and rented the place for April, 1966 at a cost of $2,500. The result was the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. Follow the links or pick up any Velvets tome to get the full account of the E.P.I.--I'll limit my quotations to descriptions of the atmosphere at the Dom itself.

From Popism: The Dom was perfect, just what we wanted--it had to be the biggest discotheque dance floor in Manhattan, and there was a balcony, too. We sublet it immediately from Jackie and Rudi...then we signed a few papers, and the very next day we were down there painting the place white so we could project movies and slides on the walls. We started dragging prop-type odds and ends over from the Factory [projectors, lights, a mirror-ball, etc.]...Of course, we had no idea if people would come all the way down to St. Marks Place for night life. All the downtown action had always been in the West Village--the East Village was Babushkaville. But by renting the Dom ourselves, we didn't have to worry about whether "management" liked us or not, we could just do whatever we wanted to. And the Velvets were thrilled--in the Dom, the "house band" finally had a house. They could even walk to work...We all knew something revolutionary was happening, we just felt it. Things couldn't be this strange and new without some barrier being broken. "It's like the Red Seeeea," Nico said, standing next to be one night on the Dom balcony that looked out over all the action, "paaaaarting." All that month the limousines pulled up outside the Dom. Inside, the Velvets played so loud and crazy I couldn't even begin to guess the decibels, and there were images projected everywhere, one on top of the other...Ondine and the Duchess would shoot people up in the crowd if they halfway knew them...The kids at the Dom looked really great, glittering and reflecting in vinyl, suede, and feathers, in skirts and boots and bright-colored mesh tights, and patent leather shoes, and silver and gold hip-riding miniskirts, and the Paco Rabanne thin plastic look with the linked plastic disks in the dresses, and lots of bell-bottoms and poor boy sweaters, and short, short dresses that flared out at the shoulders and ended way above the knee.

From Factory Made: Those three weeks at the Dom became a participatory nonstop party. Barbara Rubin invited Allen Ginsberg to join in, and he would chant Hare Krishna; Walter Cronkite and Jackie Kennedy stopped by to see what was happening with the new generation; and TV crews showed up. The poet John Ashbery, who had been away in Paris during the rise of intermedia, found himself utterly disoriented. "I don't understand this at all," he said, and burst into tears.

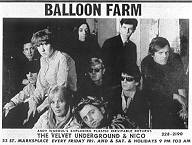

Stories conflict as to how the EPI ended its initial stint at the Dom. According to Sterling Morrison's interview in the March 6, 1970 issue of Fusion [reprinted in All Yesterday's Parties (Cambridge: Da Capo, 2005)], the Velvets were supposed to have a three-year lease on the Dom, but upon returning to New York after a mid-'66 tour, "[W]e went back to our room since that was our thing. We owned it for three years, and when we came back we discovered it was now called the Balloon Farm. Actually our lease had been torn up and the director of the Polish home had been bribed and bought off and so our building had been taken away from us."

Popism and Factory Made make no reference to a three-year lease. "The experience of playing in the heat of Chicago in a club that had no air conditioning didn't go over too well with the E.P.I.," says Warhol in Popism, "and since the Dom didn't have air conditioning either, Paul told Stanley [Tolkin] that we would wait and rent it again when it got cool...In the fall when Paul went back to rent the Dom, Stanley told him sorry, it was already rented. Al Grossman and Charlie Rothchild opened it as the Balloon Farm and asked the Velvets to play there anyway--upstairs--and they did, since they didn't have anything else to do. In the basement there was a bar with a jukebox, and Paul managed that, off and on, into the next spring and charged admission." Nico began a solo engagement downstairs at Stanley's, initially singing to cassette-taped backing tracks of the Velvet Underground, but eventually accompanied by a series of guitarists, including "Tim Buckley, Jackson Browne, Steve Noonan, Jack Elliot, Tim Hardin--[Paul] promising them they could do a set alone if only they'd play a little for Nico while she sang."

I haven't been able to locate much info on the Balloon Farm incarnation of the club. Supposedly its name came from a comment Bob Dylan had made about seeing imaginary cartoon speech balloons above the patrons' heads--since Albert Grossman was Dylan's manager I guess it could be true. In turn, the band behind one of '67's wickedest nuggets, "A Question of Temperature," apparently did name themselves after the club--but I'm not sure if they ever played there. The Mothers of Invention did, but apart from them and the Velvets I haven't been able to track down other performers. And at some point the club may have reverted to its old moniker--the best VU site lists a Dom engagement from March 15-22, 1967.

At any rate, the Grossman era was short-lived. Sometime in mid-1967 (dates conflict but are usually cited in the May-July period) he sold his lease to Jerry Brandt, who oversaw its transformation into the Lower East Side's premier psychedelic ballroom--the Electric Circus. According to A. M. Nolan's Rock and Roll Road Trip (New York: Pharos, 1992), Brandt was a William Morris agent-turned-impresario who "created an overwhelming environment of loud music, light, and strangely costumed revelers. Many top rock groups performed here but their shows were a sideshow event; the club was the star." Perry and Glinert's Fodor's Rock and Roll Traveler USA (New York: Fodor's, 1996) states that the club's first booking was "the Alternative Legal Entertainment Experiment, a show of acrobats, astrologers, and clowns." From Joel Lobenthal's Radical Rags: Fashions of the Sixties (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990):

[T]he Electric Circus became New York's ultimate mixed-media pleasure dome. Its hallucinogenic light baths enthralled every sector of New York society. "When you're finished with reality, come up here," invited Jerry Brandt, twenty-eight-year-old owner of the club. Borrowing further from the West Coast culture, the Electric Circus was populated with roustabouts of the annual "Renaissance Fairs" of San Francisco and Los Angeles. Life reported, "Magnified images of children in a park, a giant armadillo or Lyndon Johnson disport themselves on the white plastic sculptured expanse of the tent-like ceiling. Gigantic light-amoeba rove among the images, pulsating and contracting with the relentless beat of a rock band...A young man with the moon and stars painted on his back soars overhead on a silver trapeze, and a ring juggler manipulates colored hoops and shaggy hippies who unconcernedly perform a pagan tribal dance...Stoboscopic lights flicker over the dancers, breaking up their movements into a jerky parody of an old-time Chaplin movie. But then loud, loud, the hippies' national anthem, the Beatles' 'A Day in the Life,' begins, and there is stillness, reverie."...[In the club's on-site boutique], "Clothes, Furbelows, Feathers, and Astonishments," were all purveyed.

From Brewster and Broughton's Last Night A D.J. Saved My Life (New York: Grove Press, 1999): After financing the club with an audacious scheme in which the Coffee Growers' Association contributed $250,000, provided coffee was the main drink served in the club, he brought in Ivan Chermayeff who had designed the America Pavilion at the World's Fair. The designer transformed Electric Circus into a giant Bedouin tent comprised of white stretch yarn. Projections of home movies, liquid lights and morphing glutinous blobs glowed on the fabric. A gigantic sound system blasted rock freakouts to the St. Vitus dancers. The Electric Circus trumpeted itself as "the ultimate legal experience" yet it was far from it. Drugs were rife...[The club] was immortalized in Coogan's Bluff as the Pigeon-Toed Orange Peel Club, where Clint Eastwood chases an errant hippie prisoner into this den of iniquity. He soon collapses in a stoned stupor as the lights pulse and throb around him.

Brandt had clearly taken some multimedia cues from the E.P.I., but he had more sensory-overload resources at his disposal. From Popism: The difference between the E.P.I. and the Electric Circus sort of summed up what had happened with Pop culture as it moved from the primitive period into Early Slick...The year before we'd had to pioneer a media show out of whatever we could improvise from whatever we had lying around--tinfoil and movie projectors and phosphorescent tape and mirrored balls. But suddenly, during the '66-'67 year, a whole Pop industry had started and snowballed into mass-manufacturing the light show paraphernalia and blow-your-mind stuff. And a good general example of how much things had changed in such a short time is "Eric's Fuck Room." With us, this was just a small alcove off the side of the dance floor where we'd thrown a couple of funky old mattresses in case people wanted to "lounge," but it ended up being just a place where Eric [Emerson] hijacked girls to for sex during the E.P.I. shows; now, under the new Electric Circus management, it was transformed into the "Meditation Room," with carpeted platforms and Astroturf and a health food bar.

A 1969 article discussing the "psycho-theological" aspects of the club is reprinted here.

I've been having a hard time nailing down names/dates of specific performers at the Circus, but here are a few:

The Seeds, July 17, 1967--Jimi Hendrix was in the audience.

The Chambers Brothers, though I'm not sure when.

The Voices of East Harlem, whom Brandt managed--also not sure of the date(s).

Morton Subotnick was the club's director of electronic music from '67-'68.

Clear Light did a week-long engagement opening for Timothy Leary--again, not sure when.

The Grateful Dead, May 7-9, 1969.

Think Dog, sometime in 1968.

The Paupers from Toronto played there in September of 1968.

Terry Riley in 1969.

Blues bassist Johnny Ace recalls a series of blues concerts there in 1969, featuring Freddie King, Slim Harpo, Muddy Waters, Buddy Moss, and the Chicago Blues All-Stars.

[UPDATE 1/6/2007: Not particularly rock and roll in scope, but I was tickled pink to learn that Halston organized a retrospective fashion show honoring Charles James at the Circus on December 16, 1969. I imagine James' swellegant '40s/'50s evening gowns clashed mightily with the psychedelic madness of the Circus' decor. This tidbit was gleaned from Halston, edited by Steven Bluttal (London: Phaidon, 2001).]

The Flamin' Groovies, sometime in January 1970.

The James Gang had a "bummer gig" there during the summer of 1970.

The post-Reed Velvet Underground did a two-night stand on January 29-30, 1971.

The Stooges, June 1971, with Iggy covered in silver paint and glitter and upchucking all over the place--read all about it in McNeil and McCain's Please Kill Me (New York: Grove Press, 1996).

There have got to be many other names to uncover, but I've spent way too much time on this entry already--must...move...on...

Brandt may have envisioned opening a string of Electric Circuses worldwide; at any rate, he managed to open a second Circus in Toronto. But the original Circus eventually left town. According to Terry Miller's Greenwich Village and How It Got That Way (New York: Crown, 1990), "In March 1970 a small bomb exploded on the dance floor, injuring seventeen people, and the Electric Circus never recovered from the adverse publicity that followed." (An article in the East Village Other implicated that the bomb was planted in protest of the club's high admission prices--a whopping $4.50!) An architect quoted in Anthony Haden-Guest's The Last Party (New York: William Morrow, 1997) attributes the club's demise to an unattractive redesign by Charles Gwathmey. Whatever the culprit--which was probably just the march of time and tastes--the Electric Circus closed in September, 1971. [I'm not quite sure when Stanley's closed.] Brandt embarked on various other projects, including managing Carly Simon and Jobriath, running other short-lived clubs and an early designer jeans boutique, producing a flop Broadway musical called Got Tu Go Disco (I can still recall its relentless TV ad campaign), and opening the Ritz, which went on to become one of the top live venues of the '80s (to be covered in a future entry).

As for 19-25 St. Marks--the complex apparently saw sporadic use as a performance space until the late '70s, when it was bought by Reverend Joyce Hartwell for her All-Craft Foundation Center, a multipurpose community center for recovering alcoholics and drug addicts. [When I was younger and had a cuter butt, I'd sometimes get goosed by mischievous young hooligans hanging out in front of the place as I walked by.] A Tim Buckley fansite has some pics of the Center's long-time blue-and-white exterior (scroll down a bit), while Julian Cope's Head Heritage psych site reports that some architectural elements from the Electric Circus remained intact inside the building as of the '80s. But as my super-nostalgic Pops would say in his exemplary Noo Yawk accent, "No more...thing o' the past...an era gone by." The Center went bankrupt in 2000, whereupon the complex was acquired by developer Charles Yassky. It was completely gutted and refurbished (the bricks on its new facade apparently came from a disused upstate mill, according to the NY Songlines site), and is now a mini-mall of sorts, housing a number of chain restaurants.

UPDATE 10/15/2007: Add Michael Brown proteges Montage to the list of Circus performers, according to this Vance Chapman interview on 60sgaragebands.com: "I was nervous about The Electric Circus because it was a huge place that normally featured some pretty hard-rock bands, and I felt that we'd be too mellow for the crowd. But to my amazement, they were thrilled with every song we did. Our last song of the night was a cover of The Beatles' “Hey Jude.” At the end of that song the entire crowd was up to the edge of the stage, clapping their hands over their heads while they sang along with the "na-na-na" part. I couldn't believe my eyes and ears."

[UPDATE 5/25/2010: Here's an image of the Circus' interior that I got from cheapocheapo's tumblr. I'm sure this pic is in one of my books, possibly Last Night a DJ Saved My Life IIRC, but I didn't scan it at the time the entry was written. Also, NYCDreamin' located an image of a Circus poster a while back.]

UPDATE 6/1/2010: Here's the text of an ad I found in the June 22 and 29, 1967 issues of the Village Voice, announcing the opening of the club. I'll type it as it appeared, in capitals and with line-breaks intact:

DARLING DAUGHTERS

SWEET MOTHERS DANCE

BLACKLIGHT DYNAMITE

ACROBATS ASTROLOGERS

JUGGLERS FREAKS CLOWNS

ESCAPE ARTISTS VIOLINISTS

GROK GRAPES GRASS

UPS DOWNS SIDEWAYS

COFFEE THINK TANK

AIR CONDITIONED

IN MORE WAYS THAN ONE

THE ULTIMATE LEGAL

ENTERTAINMENT EXPERIENCE

THE ELECTRIC CIRCUS

OPENS JUNE 28, 1967

23 ST MARKS PLACE NYC

EAST VILLAGE

THINK ABOUT IT

UPDATE 6/3/2010: I posted a bunch of 1967 Electric Circus ads here.

UPDATE 6/10/2010: I also posted some ads for the Balloon Farm and the Dom.

UPDATE 6/25/2010: Here are a bunch of 1969 Electric Circus ads.

UPDATE 11/18/2011: Please see the revised and updated posts on 1967 ads for the Dom and the Balloon Farm and the Electric Circus.

UPDATE 3/15/2012: Here is the revised and updated post on 1969 Electric Circus ads.

UPDATE 9/18/2013: The Bedford + Bowery blog did a cool feature on the Electric Circus, replete with stories from some folks who played there.

UPDATE 12/8/2014: Marky Ramone has a book coming out next month. As part of the advance publicity, Bedford + Bowery did a cool post on his favorite East Village clubs of yore, including the Electric Circus.