In a feeble attempt to combat my constant homesickness, I compile tales of New York City rock & roll landmarks, most of 'em long gone. Moronic musings on various other enthusiasms are also thrown in for good measure.

Friday, November 18, 2005

Thursday, November 17, 2005

Unga-wah!

In 1966 and '67, when out-of-town bands came to NYC, they would do shows at places like Ungano's and the original Peppermint Lounge, that were really holdovers of the Copacabana era and not so very unlike this "vibe" (maaaan) at all. [He's referring to the scene at the Hard Rock Cafe during its launch party for Little Steven's Underground Garage.--Ed.] (Once they turned on the three-dollar color-wheel lights, that is.) The only difference here is that the Hard Rock Cafe has a fifty-foot ceiling and the lights cost three THOUSAND dollars each.

According to featbase.net, a site devoted to Little Feat (who played there on January 4, 1971), it was a "basement club" with an occupancy of 200; "[it] closed around March 20, 1971, and then reopened on Staten Island as Ungano's Ritz around May 21, 1971." This second venue was in an old 2,000-seat movie house, the Ritz Theater, at 251 Port Richmond Avenue.

Both the club and the theater attracted a surprisingly impressive array of the era's talent, including:

- The MC5--their NYC debut, on the heels of a junior high gig in Great Neck, L.I. a few nights before. This MC5 page contains the text of a 1969 Changes article by Mike Jahn, offering a rare physical description of the club: "Ungano's is an average size club with a big back room checked off by four mirrored pillars. The stage is along one wall. Opposite it is a small raised gallery for the press. It takes a club with imagination to put the press in a raised gallery with a Dayglo light that makes their underwear show through their clothes."

- The Stooges

- The Flamin' Groovies

- The Kinks

- Badfinger--see more memories and photos here and here.

- The Vagrants

- Mountain--Jimi Hendrix jammed at a couple of their shows in September 1969, once playing Felix Pappalardi's right-handed bass upside down. Another Hendrix jam session at Ungano's is described here.

- Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band

- The Allman Brothers--NYC debut, August 4-6, 1969, and more gigs in 1970.

- The Grateful Dead

- Tony Williams' Lifetime, featuring John McLaughlin, Jack Bruce, and Larry Young.

- Fleetwood Mac

- Uriah Heep

- The Faces

- Chelsea (Not to be confused with the British punk band of the same name--these guys included Peter Criss, pre-KISS.)

- Van Morrison

- Golden Earring

- Black Sabbath

- Bird bands Crow and Raven

- The Heard--never *heard* of 'em, but the pics at this link are super-cool.

- Plum Nelly

- Free

A Staten Island local on cinematreasures.org remembers seeing "Alice Cooper, Mountain, Black Sabbath, Yes, Capt. Beefheart, MC5, King Crimson, The Kinks, Fleetwood Mac, Deep Purple...even Vanilla Fudge" at Ungano's Ritz. He adds, "The Ritz concerts did not last to due 'contract riders' put into place in the early seventies by NYC concert promoters. They insisted that the musicians performing at their place could not book additional shows within a 50 mile radius of the venue nor within a month surrrounding the show. This essentially killed the bookings for national recording acts at the Ritz Theater." Apparently the building went on to become a roller rink, but since 1985 it has been occupied by Pedulla Ceramic Tile. What became of the basement of 210 W. 70th Street is unclear. The building as a whole was, and may still be, the Bradford Hotel, but seems to also house various other businesses.

[UPDATE 5/6/2010: Here are a couple of Ungano's ads unearthed by a long-time Internet pal of mine, the eagle-eyed Rob B. Jeez, this piece seems skimpy--I should really see if more info has come forth. The daughter of one of the proprietors contacted me quite a while ago, offering answers to any questions I might have...unfortunately I was too shy and too preoccupied with non-blog matters at the time to fully take her up on it, and I fear the offer may have expired by now.]

UPDATE 3/15/2012: Here is a revised and improved post on 1969 Ungano's ads.

Rockin' the Para--uh, mount, toniiiiiite!

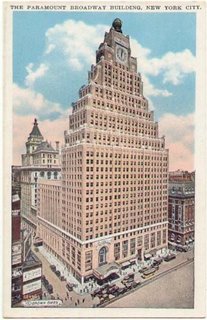

(NEW YORK) PARAMOUNT THEATRE--in the Paramount Building, 1501 Broadway between 43rd and 44th Streets. There's no need for one of my usual redundant recaps on the Paramount Theatre's history--cinematreasures.org's Paramount Theatre page contains a surfeit of lore galore, plus further links to photos and movie screening ads. Can't resist poaching a few pertinent quotes, though:

The Paramount was the first great movie palace in New York City that was built in the "Chicago-style" pioneered by the architectural firm of Rapp & Rapp. When first opened in 1926, its extravagant French Renaissance interiors were a radical change from the restrained Adam and Empire styles that New Yorkers had become accustomed to at the Paramount's main rivals, the Strand, Capitol, and Loew's State (all designed by Thomas Lamb). The Paramount became one of the city's top tourist attractions, but not for long due to the 1927 opening of the Roxy, which was almost twice as large and even more spectacular...For a theatre of its size (3,664 seats), the Paramount was one of the narrowest ever built because the auditorium had to be squeezed between two adjacent buildings--the Paramount office tower, which faced Broadway, and the headquarters of The New York Times (229 West 43rd Street). Consequently, the Paramount Theatre's entrance and a short lobby were carved out of the Paramount Building. After you passed through that short lobby, the actual theatre building began with the Grand Lobby, where you found yourself at the rear of the auditorium, which ran parallel to Broadway with the stage wall backing on West 44th Street. The main floor had only four sections of seats. Above that was a separate and recessed mezzanine with boxed seats. And one level above the mezzanine was the steeped balcony, divided into five sections of seats across and four from front to back. Due to the narrowness of the auditorium, the Paramount also had a narrow stage opening that proved a problem throughout the theatre's lifetime. Stage productions had to use the orchestra lift as part of the show or erect small platforms next to the pit. When the wide screen era arrived, some of the procscenium had to be removed to accommodate it...

The lobby was modeled after the Paris Opera House with white marble columns, balustrades and an opening arms grand staircase. Inside, drapes were red velvet, the rugs were a similar red. The theater also had a grand organ, and an orchestra pit that rose up to the stage level. The ceilings were fresco and gilt. The railings were brass, and the seats plush. There were Greek statues and busts in wall niches. The rest rooms and waiting rooms were as grand as any cathedral. In the main lobby there was an enormous crystal chandelier.

[Side note: these pages on early Times Square signage mention the previous structure on this site, the Putnam Building--named in honor of General Israel "whites of their eyes" Putnam. Supposedly he and George Washington met at this spot during the Revolutionary War.]

Famed as much for its stage shows as for its films and sumptuous decor, the Paramount boasted a long list of legendary performers, including Mary Pickford, Bing Crosby, Benny Goodman (with Gene Krupa on skins), Cab Calloway, Woody Herman, Duke Ellington, Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, Perry Como, Eddie Fisher, Erskine Hawkins, the Treniers, Martin and Lewis (and apparently Jerry had worked as a Paramount usher in the early '40s), Peggy Lee, Tony Bennett, Vic Damone, Joey Bishop, Les Paul and Mary Ford, the Mills Brothers, Louis Prima and Keely Smith, Imogene Coca, and Jackie Gleason with his "Honeymooners" cohorts, among many others. Fine as these folks were, none of them caused quite as much of a stir as Frank Sinatra, who played several multi-date engagements to hordes of screaming, swooning, street-blocking bobby-soxers in the early '40s.

Alas, the theater's rock & roll connections concern us most here. Such events were few and far between, but fun.

Elvis never made an appearance, but his 40-foot-tall, guitar-slung likeness was mounted above the marquee for the November 15, 1956 premiere of Love Me Tender.

Although Alan Freed's association with the Brooklyn Paramount is more well-known, he did put on a few of his extravaganzas at the Manhattan location. Some researchers confuse the two venues, which has made ascertaining the correct dates a bit difficult.

- The earliest appears to have taken place in February 1957, in conjunction with the premiere of Don't Knock the Rock. The bill included the Platters, Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers, Ruth Brown, Nappy Brown, the Cleftones, the Cadillacs, and the Duponts, which featured a pre-Imperials Little Anthony Gourdine.

- Not absolutely sure of the dates for this show, but I believe it happened in early July, 1957--Chuck Berry, Clyde McPhatter, the Moonglows, Big Joe Turner, the Everly Brothers, Johnny & Joe, Paul Anka, LaVern Baker, Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers, his brother Lewis Lymon with the Teen Chords, Jodie Sands, Screamin' Jay Hawkins, and Terry Randazzo.

- From December 26, 1957 through January 6, 1958, the "Christmas Jubliee/Holiday Show of Stars" featured Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers, the Rays, Paul Anka, Danny & the Juniors, Lee Andrews & the Hearts, the Teenagers (I guess Frankie L. went solo by then), Jo Ann Campbell, and the Rays. Seems this show broke Frankie Sin's house record!

Here's a pic of the statuary management put in storage before these bookings in an effort to prevent rowdy teens from toppling them. And here's a pic of said delinquents dancing in the aisles and on seats. Be sure to consult the archives section of alanfreed.com--especially the "newspaper articles" link, loaded with vintage scans about these events.

[Side note # 2: While Freed booked most frequently at the two Paramounts, he also utilized the Brooklyn Fox (10 Flatbush Avenue), the Academy of Music, Loew's State (1540 Broadway), Loew's Paradise (2413 Grand Concourse in the Bronx--which hopefully won't meet a Stygian fate), the St. Nicholas Arena in Harlem, the Sussex Avenue Armory in Newark, and the New York Coliseum (10 Columbus Circle, demolished; now the site of the Time Warner Center).]

[UPDATE 2/7/2007: The Game Show Network recently aired a '50s episode of To Tell the Truth with Alan Freed as one of the contestants. It must have been originally aired around the time of the 57/58 Holiday Show of Stars, because some references were made to broken house records--not to mention broken house seats and other damage sustained by the Paramount in the wake of those raucous record-breaking delinquents. The panelists, including Polly Bergen, Ralph Bellamy, Kitty Carlisle, and Hy Gardner, clearly had an anti-rock & roll bias--I mean, jeez, the man had been in three movies by then and they didn't recognize him? Still, Bellamy and Carlisle correctly identified him as the real Freed. Polly Bergen chose one of the impostors because he knew the Paramount's manager was named Bob Shapiro.]

A cinematreasures.org regular posted the following: "For the Easter holiday period in 1964, the Paramount presented what the press reported as the theatre's first stage show in seven years. It was a Rock-N-Roll revue emceed by the radio deejays known as the 'WMCA Good Guys.' The performers included Sam Cooke, Dean & Jean, Rufus Thomas, the Devotions, the Sapphires, the Four Seasons, Terry Stafford, Chris Crosby, Diane Renay, and King Curtis & Band. There were five stage shows per day, punctuated by screenings of Zenith International's "No, My Darling Daughter," a British comedy with Juliet Mills and Michael Craig. The engagement ran from March 27 through April 5." Another cinematreasures guy remembers seeing Lesley Gore and James Brown at one of these shows. "Dandy" Dan Daniel offers some memories of those shows in this obit for his former fellow Good Guy, Dean Anthony.

Just when I thought I couldn't possibly learn anything new about the Beatles, along came another factoid. As if to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Frankie's fervent '44 fanbase, the Fab ones caused further screaming to echo off the Paramount's proscenium on September 20, 1964. Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme, of all people, were the opening act. All proceeds went to the United Cerebral Palsy and Retarded Infants Services charities--and this was the sole benefit concert the lads did in the U.S.

[UPDATE 7/20/2006: According to Norton Records' required-reading Mary Weiss interview, the Shangri-Las were also on this bill!!!]

[UPDATE 9/29/2007: Mary offers some further memories of this gig in a NY Sun interview.]

[UPDATE 6/9/2010: Oh my, am I late to the party on this one. Over a year ago, an NYC photo-blogger ("what about the plastic animals?") located the remnants of an old poster on the side of a Harlem building that was undergoing renovations at the time. It advertised a Dave Clark Five show at the Paramount, emceed by Murray the K. The blogger couldn't ascertain a concert date, but according to this DC5 chronology, it must have been on October 31, 1964.]

In May, 1965, coinciding with the engagement for Harlow (one of two Jean Harlow biopics released that year, this one starring Carol Lynley), local dance-party TV show host Clay Cole put on a revue featuring several soulful acts--Mary Wells, the Marvelettes, Ronnie Dove, Tony Clark, Charlie & Inez Foxx, and the Gypsies.

[UPDATE 2/14/2007: While researching an entry on the Brooklyn Fox, I came upon this auction site page featuring a number of '60s concert programs for sale, including three for shows held at the Paramount:

- The aforementioned WMCA Good Guys "Easter Parade of Stars" in 1964, with James Brown, Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson, Bobby Rydell, Lesley Gore, the 4 Seasons, King Curtis, Chris Crosby, Dean & Jean, American Beetles, Rufus Thomas, the Sapphies, Diane Renay, Ruby & The Romantics, and Terry Stafford.

- Another WMCA Good Guys event called the "Show of Shows," with the Animals, Bobby Rydell, Del Shannon, Jan & Dean, Elkie Brooks, the Dixie Cups, Sam "The Man" Taylor, Ronnie Dove, Dee Dee Sharp, The Chartbusters, and Ronnie Dayton. The dates aren't given, but this site suggests that it occurred during Labor Day week in 1964.

- A "10-Day Easter Show" hosted by Soupy Sales in 1965, with the Hullabaloos, the Detergents, Shirley Ellis, Little Richard, the Vibrators {sic.--should probably be the Vibrations}, the Exciters, the Hollies, the Uniques, Dee Dee Warwick, Roddy Joy, Sandie Shaw, and King Curtis.] [UPDATE 3/22/2009: Found these images from the program.]

[UPDATE 5/27/2010: In a BBC Radio 2 documentary originally broadcast on 5/26/2010, Allan Clarke and Bobby Elliott recalled that Jimi Hendrix was playing for Little Richard's band at the time...but that Penniman was let go and forcibly removed from the premises at a certain point, for refusing to cut his set down to two songs.]

The Paramount closed later that year; Thunderball was the final flick shown. The auditorium and lobby sections were gutted and remodeled as office space, most of it serving as an annex to the adjacent New York Times headquarters. (The theater's renowned Wurlitzer organ survived and eventually found its way to Wichita, Kansas.) In the early aughts, the World Wrestling Federation operated a theme restaurant on the lower level of the building, where the theater's lounges and restrooms had previously been located. To spruce up the entrance, the WWF funded the construction of a replica of the Paramount's original marquee design. Though fans were presumably pleased that they now could actually smell-ell-ell-ell-ell what the Rock was cookin', the wrasslin' restaurant didn't last very long. As of August, 2005, the space became the new home of the Hard Rock Cafe. In a related-in-name-only twist, plans are afoot to convert the nearby Paramount Hotel (235 W. 46th Street) into the city's first Hard Rock Hotel by Spring 2006.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Anachronistic minds think alike

Most of the time, I walk around in a meta-historical haze, my spirit tossed between musical decades — haunting some imaginary Brill Building of the soul, then reclining in the hair of Marc Bolan and then — occasionally — being drawn back to the future by a contemporary artist of real imagination and talent. So there’s nothing like a great band pulling a stunt like this to remind me, You’re actually alive, now, at this precise moment in history.

Not that I'd necessarily ascribe this occurrence to the White Stripes' Tegan and Sara cover record that she's reviewing in the article, even if I knew what it sounded like. In fact, such a phenomenon--getting completely bowled over by a new, non-revivalist band/record, and thus feeling somewhat in step with the times--hasn't happened to me in many a year. Yet Sullivan's enthusiasm gives me hope that this could conceivably come to pass at some point. And 'til then, there's no shame in frettin' to the oldies.

"Brill Building of the soul." Why couldn't I have come up with that line?

[Currently reading Ken Emerson's Always Magic in the Air: The Bomp and Brilliance of the Brill Building Era (New York: Viking, 2005).]

Friday, November 04, 2005

The Bow-Ties that Bond

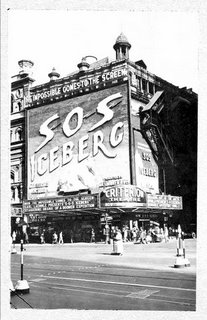

Before the Times set up shop in the area, Longacre Square was the horse dung-scented center of New York's carriage trade. An unseemly spot indeed for the future Crossroads of the World, but as the city's entertainment districts had been inexorably migrating ever further uptown along Broadway throughout the 19th century, the Square's eventual colonization by the theater crowd was inevitable. Oscar Hammerstein I was the earliest impresario to venture there. In 1895, on the site of the former 71st Regiment Armory (destroyed in a fire), he opened the Olympia Theatre, a massive Beaux Arts complex comprising a 2,800-seat Music Hall, a 1,850-seat playhouse called the Lyric Theatre, a smaller Concert Hall, and a roof garden theater. According to Anthony Bianco's Ghosts of 42nd Street (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), admission was fifty cents, and patrons could wander between the theaters at will. "[T]he Olympia did not style itself as a family entertainment venue," writes Bianco. "Content to leave the middle of the road to others, Hammerstein experimented with provocative new acts and formats that expanded vaudeville's boundaries." Hammerstein's adventurous fare included operas (some of which were his own compositions), "Living Pictures" (tableaus presented partially in the nude), Isham's Octaroons (an African-American song-and-dance troupe), and a notoriously so-bad-they're-good act called the Cherry Sisters. Unfortunately, not every production he put on was a financial success, which led to a foreclosure on the property after only three years of operation. The building was auctioned off, and the theaters became separate entities under the auspices of different producers. Hammerstein's next local enterprises, the smaller-in-scale Victoria and Republic Theatres, were more lucrative. Meanwhile, the Music Hall was renamed the New York Theater, and was converted into a movie/vaudeville house when Loew's took it over in 1915. The Lyric was first renamed the Criterion, then became a movie house called the Vitagraph in 1914, only to revert to the Criterion moniker a couple of years later. In 1907, Flo Ziegfeld staged his first production of Follies at the rooftop garden theater, renamed Le Jardin de Paris. When he decamped for the New Amsterdam in 1913, the roof garden was converted into a dancehall called Jardin des Danses. Despite its many virtues, the magnificent Olympia building did not outlast the Depression; it was demolished in 1935.

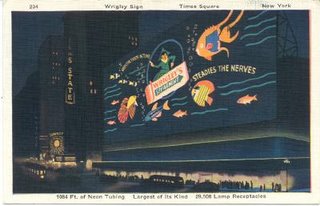

A year later, the Criterion Building rose in its stead. It occupied the same block-long frontage, but was not nearly as tall as its predecessor--unless you include the height of its huge rooftop neon sign, a fish-festooned spectacular advertising Wrigley's Spearmint Gum.

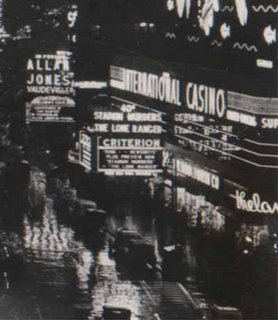

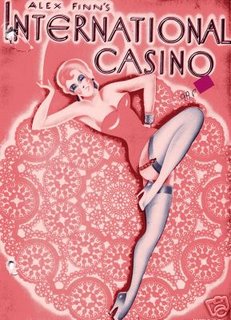

The building featured a new Criterion movie house (designed by Thomas Lamb and Eugene de Rosa), ground-level retail space, and a fabulous Art Deco nightclub/restaurant called the International Casino. According to Susan Waggoner's Nightclub Nights: Art, Legend, and Style, 1920-1960 (New York: Rizzoli, 2001), this Casino had nothing to do with gambling:

Once one passed through the solid brass doors and into the red and gold mosaic lobby, there was no shortage of amusements. The Cosmopolitan Salon was fitted with a small stage and littered with settees that could accommodate nearly eight hundred. Another one hundred and sixty could quench their thirst at the Spiral Bar, a curved slide of polished mahogany that swept from the ground floor up to the mezzanine. All this was a mere warm-up for the main room, where tiered platforms assured all fifteen hundred diners an unobstructed view of the show.

The show, mounted on an elaborately high-tech motorized stage, featured such delights as "novelties from five continents and the beauties of ten countries," an orchestra "whose reed section might suddenly plunge from sight, like riders on a parachute drop," a fanciful "Ice Frolics" revue, comedians like Milton Berle, and gorgeous chorines with gams for days. The swank Streamline Moderne surroundings were "designed by Donald Deckie, who later designed the Radio City Music Hall," according to Anthony Haden-Guest's The Last Party (New York: William Morrow, 1997). However, the Casino may have been too gloriously grandiose for its own good; much like the Olympia, it closed after a mere three years in business.

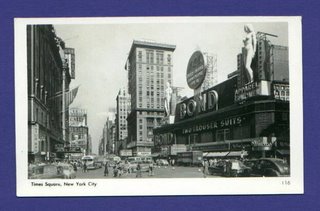

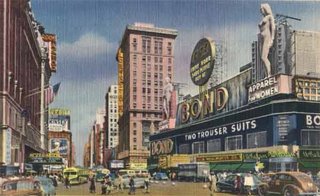

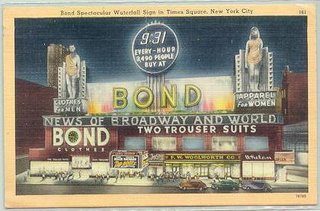

Bond Clothes took over the Casino's space in 1940, moving from its previous location adjacent to the Palace Theater a couple of blocks north. In its new digs Bond styled itself as the world's largest men's haberdashery, and offered some women's wear as well. As if the store's famous "TWO TROUSER SUITS" neon sign weren't enough, beginning in 1948 it also boasted the most splendid spectacular ever to grace the Great White Way, designed by Douglas Leigh for Artkraft-Strauss. As described in Leigh's 1999 Times obituary:

At the base of the Bond sign was an electric news zipper, about five feet high, running along the entire facade. In Mr. Leigh's design, twin 50-foot-high figures, one male and one female, flanked a waterfall 27 feet high and 120 feet long. Strands of electric lights seemed to clothe the chunky classical figures at night, but by day they appeared naked.

Those loincloth-lights were added only after guests at the Hotel Astor across the street complained about the statues' scandalously starkers state. A clock poised above the waterfall perpetually reminded the public, "EVERY HOUR 3,490 PEOPLE BUY AT BOND." (I suppose an even 3,500 customers per hour would have been too much to handle...)

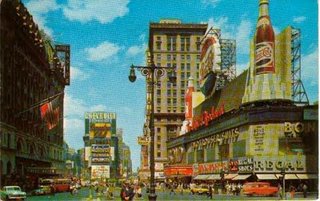

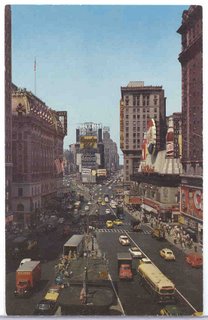

After six good-looking years, the sign was replaced with a Pepsi ad; the waterfall remained (and kept gushing until the early '60s), but was now flanked with giant Pepsi bottles. Apparently a Chevy ad was once meant to take Pepsi's place, but a garagantuan Gordon's Gin bottle and a smoking Winston man (a total Camel sign rip-off) eventually appeared there instead. The ground-level storefronts evolved over time as well--among the successive occupants were Woolworth's, Whelan Drugs, King of Slim's Ties, Loft's Candy, Regal Shoes, Disc-O-Mat Records, tourist tchotchke outlets, and those ubiquitous bad-deal '70s/'80s electronics stores.

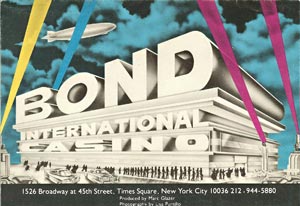

Bond Clothes sold its last two-trouser suit in 1977, and after a couple of vacant years, the space was respectfully rechristened as Bond International Casino, supposedly the largest disco the world had yet seen. As described in The Last Party, the club was co-owned by John Addison and Maurice Brahms. It opened in July 1980, and featured such accoutrements as a "musical staircase," fountains retrieved from the set of The Liberace Show (which often ended up filled with near-naked patrons), and a wide-ranging music policy (usually spun by resident DJ Kenny Carpenter). However, according to these opinionated folks on discomusic.com, the joint never quite caught on, for various reasons--bad location (Times Square at the height of its sleazy-seedy era), poor acoustics, lack of an atmospheric theme, inconsisent musical choices, and above all, too much space to fill on a nightly basis.

There were no such space-filling difficulties during the Clash's booking in May-June, 1981. The buzz surrounding their initial eight-night stand was so high that the shows were dangerously oversold--3,500 tickets for each night, at a venue with a legal capacity of about 1,800. The FDNY threatened to shut the place down following the first two overcrowded nights. After much negotiation with city authorities, the band worked out a deal wherein they would play as many shows as it would take to honor all ticket holders--an unprecedented seventeen concerts. Times Square hadn't seen that much commotion since Frankie at the Paramount, or V-J Day. An incredibly and obsessively detailed day-by-day account of the residency is provided at blackmarketclash.com (click on the link for 1981, then click on each Bond's date). Also check out the Westway to the World DVD, which includes Don Letts' documentary footage of Bond's. And dig these articles by Ira Robbins and Jonathan Lethem.

I've found references to only a few other rock shows, including Wendy O. Williams (yes, a car was blown up), the Blues Project (I don't recall Al Kooper mentioning this one in Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards), Blue Oyster Cult, and a one-off night featuring members of Blondie and Chic. It's unclear just when Bond's closed, or what, if anything, occupied its space from the mid-'80s to the mid-'90s--but the neon BOND sign remained in place for quite some time.

The Criterion Building still exists, but it looks nothing like it did in the old postcards. Now called the Bow-Tie Building (a reference to the shape of the Times Square intersection when viewed from above), it's owned by members of the same Moss family who have had interests in the structure since its 1936 inception. The Roundabout Theater Company rented space in the building through much of the '90s, but I'm not sure which part they used. The Criterion Theater, which spent its last few years as a much-maligned multiplex, closed in 2000. Most of the building is now occupied by the flagship Toys R Us, a Foot Locker, and a Swatch emporium. There's no BOND sign facing Broadway anymore, but if you go around the corner on 45th, you'll find a smaller facsimile on the side of the building, attached to an old school-inspired Italian restaurant called Bond 45.